©1995 N.Y. Times News Service

December 12, 1995 Tuesday, BC cycle

SECTION: INTERNATIONAL, page 4

HEADLINE: RUSSIA JOURNAL: KRISHNAS BAKE BREAD IN ONE OF RUSSIA’S BROKEN CITIES

By MICHAEL SPECTER

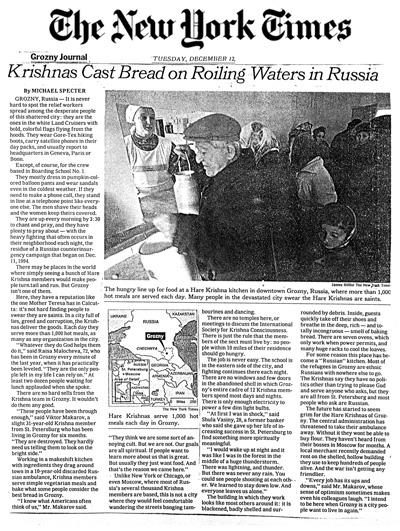

GROZNY, Russia – It is never hard to spot the relief workers spread among the desperate people of this shattered city: they are the ones in the white Land Cruisers with bold, colorful flags flying from the hoods. They wear Gore-Tex hiking boots, carry satellite phones in their day packs, and usually report to headquarters in Geneva, Paris, or Bonn. Except, of course, for the crew based in Boarding School No.1. They mostly dress in pumpkin-colored balloon pants and wear sandals even in the coldest weather. If they need to make a phone call, they stand in line at a telephone point like everyone else. The men shave their heads and the women keep theirs covered. Theyare up every morning by 3:30 to chant and pray, and they have plenty to pray about with the heavy fighting that often occurs in their neighborhood each night, the residue of a Russian counterinsurgency campaign that began on Dec. 11, 1994. -“Here, they have a reputation like the one Mother Teresa has in Calcutta: it’s not hard finding people to swear they are saints.” There may be places in the world where simply seeing a bunch of Hare Krishna members would make people turn tail and run. But Grozny isn’t one of them. Here, they have a reputation like the one Mother Teresa has in Calcutta: it’s not hard finding people to swear they are saints. In a city full of lies, greed, and corruption, the Krishnas deliver the goods. Each day, they serve more than 1,000 hot meals, as many as any organization in the city. “Whatever they do, God helps them do it,” said Raisa Malocheva, 72, who was in Grozny every minute of the last year, when it has practically been leveled. “They are the only people left in my life I can rely on.” At least two dozen people waiting for lunch applauded when she spoke. There are no hard sells from the Krishna team in Grozny. It wouldn’t do them any good. “These people have been through enough,” said Viktor Makarov, a slight, 31-year-old Krishna member from St. Petersburg who has been living in Grozny for six months. “They are destroyed. They hardly need us telling them to look on the bright side.” Working in a makeshift kitchen with ingredients they drag around town in a 10-year-old discarded Russian ambulance, Krishna members serve simple vegetarian meals and bake what some people consider the best bread in Grozny. “I know what Americans often think of us,” Makarov said. “They think we are some sort of annoying cult. But we are not. Our goals are all spiritual. If people want to learn more about us, that is great. But usually they just want food. And that’s the reason we came here.” Unlike New York or Chicago, or even Moscow, where most of Russia’s several thousand Krishna members are based, this is not a city where they would feel comfortable wandering the streets banging tambourines and dancing. There are no temples here, or meetings to discuss the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. There is just the rule that the members of the sect must live by: no people within 10 miles of their residence should go hungry. The job is never easy. The school is in the eastern side of the city, and fighting continues there each night. There are no windows and few doors in the abandoned shell in which Grozny’s entire cadre of 12 Krishna members spend most days and nights. There is only enough electricity to power a few dim light bulbs. “At first I was in shock,” said Shula Vasiny, 28, a former banker who said she gave up her life of increasing success in St. Petersburg to find something more spiritually meaningful. “I would wake up at night and it was like I was in the forest in the middle of a huge thunderstorm. There was lightning, and thunder. But there was never any rain. You could see people shooting at each other. We learned to stay down low. And everyone leaves us alone.” The building in which they work looks like most others around it: it is blackened, badly shelled, and surrounded by debris. Inside, guests quickly take off their shoes and breathe in the deep, rich – and totally incongruous -smell of baking bread. There are seven ovens, which only work when power permits, and many huge racks to cool the loaves. For some reason, this place has become a “Russian” kitchen. Most of the refugees in Grozny are ethnic Russians with nowhere else to go. The Krishnas say they have no politics other than trying to please God and serve anyone who asks, but they are all from St. Petersburg and most people who ask are Russian. The future has started to seem grim for the Hare Krishnas of Grozny. The central administration has threatened to take their ambulance away. Without it, they won’t be able to buy flour. They haven’t heard from their bosses in Moscow for months. A local merchant recently demanded rent on the shelled, hollow building they use to keep hundreds of people alive. And the war isn’t getting any friendlier. “Every job has its ups and downs,” said Makarov, whose sense of optimism sometimes makes even his colleagues laugh. “I intend to be here when Grozny is a city people want to live in again.”